Selma is most known these days for the Edmund Pettus Bridge, an icon of the Civil Rights movement — but few know that it wasn’t Selma’s only bridge across the Alabama river, and fewer still realize how new its status is. I’d like to offer a very brief history of the two bridges and a reflection on how one became an object of legend.

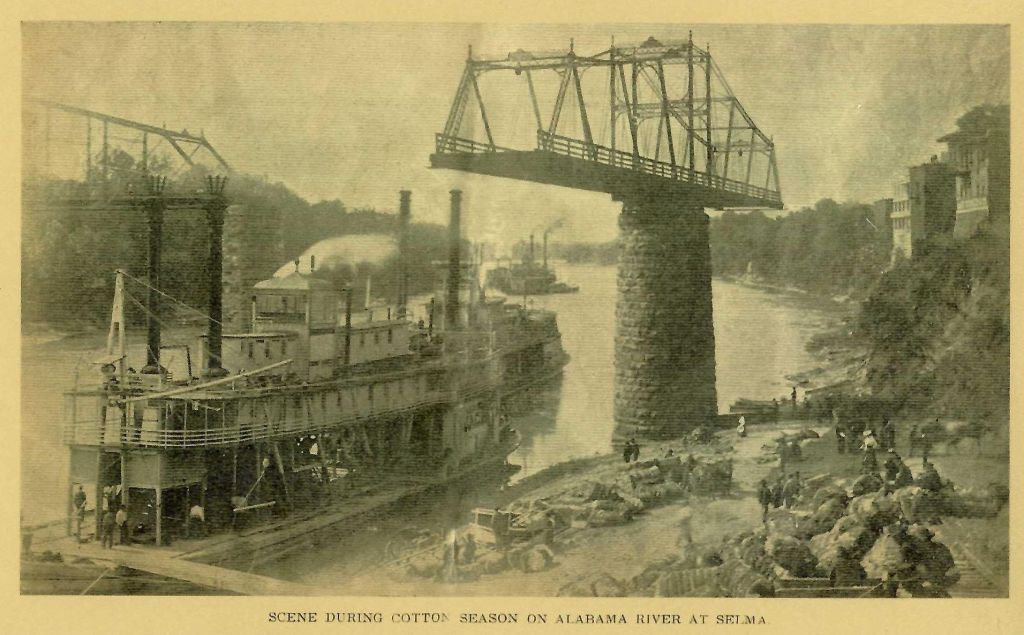

The Alabama river was bridged curiously late in the history of the city and State, some 64 years after the city’s founding. The original ‘turning bridge’, commonly called the City Bridge, ran diagonally across the river from the foot of Washington Street, and was funded by the Selma Bridge Company, a public corporation subscribed to by Selmians who viewed a bridge across the river as a matter of civic pride: the ferry simply wouldn’t do. When completed, the bridge was one of the first steel infrastructure projects in the state.1 It was officially opened on Tuesday, April 21st, 1885, though some traffic had already put it to use. 2 As hinted by the name, the first midsection of the bridge could be disconnected and swiveled to permit river traffic to progress, controlled from a building which still exists, the “Bridgetender’s House”. This would effectively close the bridge until the waiting vessels were clear — sometimes for a few minutes, sometimes up to an hour. As Selma continued booming and entered the automobile age, the turning bridge became inadequate, especially after the Montgomery Highway became US Highway 80 and auto traffic increased. Stopping traffic that consisted of a few horsedrawn wagons was one thing, but hundreds of cars an hour? A larger bridge would need to be built. The turning bridge was officially closed on May 25th, 1940: so short was its lifespan that a woman who participated in its opening in 1885, Mrs. Page Nelson Atkins, also served to officially close it, in both instances reciting the same poem.3

The new bridge was designed by a Selma native, Henson K. Stephenson, and constructed in eight months by the T.A. Loving Company of North Carolina under the auspices of the Alabama Highway Department at the cost of $863,000. Walter Jackson’s Story of Selma indicates that the bridge replacement was initiated by Governor Graves, who aimed to make it happen before he left office: such haste may explain why the buildings where the bridge was to connect to Broad Street were perfunctorily condemned and removed, rather than their owners being properly compensated via legal channels.

The bridge was named in memory of Edmund W. Pettus, an accomplished Selma attorney whose life of legal work was occasionally interrupted by calls to higher service: he served in the Mexican war, fought for southern independence, and was an active contributor to the life of Selma, helping organize its school board. He was much-loved in Selma: Walter Jackson’s Story of Selma records that the news of his election to the US Senate was met with widespread celebration bordering on bedlam, resulting in a holiday.4 He was publicly mourned on his death in 1907, and Congressman Clayton of Alabama said that no man had ever performed more services for the people than did Senator Pettus. These days, he is a victim of libelous propaganda, frequently described as a ‘grand dragon’ of the Ku Klux Klan in articles that offer no proof, and his other services are forgotten when they do not serve the desired narrative. Alston Fitts, a Selma historian who wrote Selma: A Bicentennial History, pointed out that there is ‘no concrete evidence that Pettus was ever a Klansmen, let alone a grand dragon’. 5 Pettus would have certainly had values and views that we object to today, but mind the old adage about he who is without sin casting the first stone. Pettus was no progressive or an idealist, but a man who served and fought for the community to which he was attached — and, unlike his critics, he put his life and reputation on the line, facing death in battle numerous times.

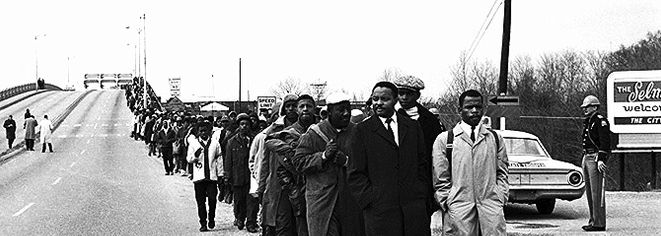

The bridge is known today not because of its striking aesthetics, but because of the role it played in the Civil Rights movement: it is as iconic to the movement as the flag-raising on Iwo Jima photo is emblematic of the Pacific War. News articles written about commemorations of the Bloody Sunday march will describe how state troopers attacked marchers ‘attempting to cross’ the bridge. This is the view of history espoused in Wallace, in which a participant of the march says that “it took us three tries, but we finally got across that bridge”. In point of fact, however, not only were marchers not attacked ‘crossing the bridge’, but crossing the bridge was not the object. No history of the movement pretends otherwise. James Bevel, a local Civil Rights leader, explicitly stated that they were borrowing from the Bible and “going to see the king”, i.e. walking to Montgomery to demand an end to voter suppression and segregation. 6 SNCC, the organizing group, was denied the right to march on the highway, officially because the state could not guarantee their safety as they marched the 50-odd miles through rural Alabama: following the usual logic of power, the marchers were beaten by men with uniforms so they would not march and risk being beaten by men without uniforms.

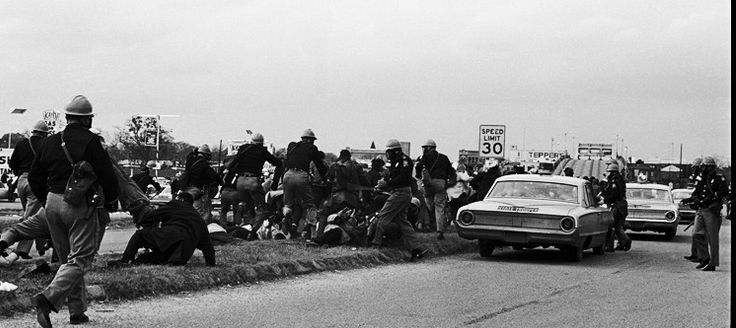

As is well known, the marchers on March 7, 1965 were confronted and physically attacked by state troopers and Sheriff Jim Clark’s ‘posse’: they were attacked, however, not on the bridge but hundreds of yards away in Selmont. Photos from multiple sources — Spider Martin, the Alabama State Troopers, etc – clearly show John Lewis and Hosea Williams peacefully leading a column of marchers across the bridge, into Selmont, and then being attacked well clear of it. Similarly, when King led the “Turnaround Tuesday” march in the days following, the marchers were again confronted (peacefully) on the opposite side of the bridge. Search the speeches of King, Lewis, Bevel, etc in vain for any mentions of Edmund Pettus: comb The Selma Movement, a collection of remembrances from participants, for mentions of Edmund Pettus and you will be disappointed. It was merely a bridge to cross, one of many between Selma and Montgomery.

I suspect the bridge did not become an object of Civil Rights iconography until the 1980s, when bridge-marching ‘reenactments’ were held, and the repeated ritual made crossing the bridge, and by extension the bridge itself, more important than the marchers’ actual object of demanding justice from Governor Wallace. It’s easy to grasp how attractive the modern story is: Civil Rights protesters defiantly marching across a bridge named for a Confederate general has enormous symbolic potential. And yet, as Fitts noted in his interview with Al Benn, there is a certain appropriateness in a march to Montgomery to demand voting rights being conducted over a bridge named after a man who supported a new constitution that concentrated power in Montgomery and denied blacks and poor whites the vote. Were the name changed, the meaning would evaporate. Personally, I suspect Pettus would be somewhat heartened by the fact that a bridge bearing his name continues to bring tourist revenue to the city he loved and served for much of his life, even if he would have objected to why said bridge serves that purpose. History sometimes has a sense of humor.

- 1937, The Selma Times-Journal. August 8. 4. ↩︎

- 1885.The Selma Times. April 18. 4. ↩︎

- 2000. The Selma Times-Journal. April 27. E8. ↩︎

- Walter Jackson, The Story of Selma (New York: Random House, 1954), 398. ↩︎

- 2015, The Montgomery Advertiser. June 29th. ↩︎

- Chuck Fager, Selma 1965: The March that Changed the South. (Durham: Kimo Press., third edition 2015.) 90. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Selma: An Architectural Field Guide | Reading Freely Cancel reply